Object-oriented design has always fascinated me because it feels so natural and intuitive. Everything I encounter—whether physical or abstract—can be seen as an object with its own properties and behavior. That’s the real strength of this approach. It helps me divide complex systems into smaller, understandable units. In this article, I’ll guide you step by step through the idea of objects in object-oriented design and show how they shape clear, maintainable, and scalable solutions.

What is Requirements Modeling

What is Requirements Modeling? In requirements engineering and IT business analysis, requirements modeling is the process of translating stakeholder needs into clear, structured representations of a system. It defines what the system should do, how it should behave, and how it interacts with users and other systems. Object-oriented design fits naturally into this process by modeling real-world entities as objects with attributes and behaviors. This approach bridges the gap between requirements and implementation, ensuring consistency and clarity throughout development.

What Is Object Orientation?

Object orientation is more than just a programming technique; it’s a powerful design philosophy. Rather than focusing solely on how something works, I shift my attention to what something is. That change in perspective makes all the difference. By doing so, I start to see systems as organized collections of interacting elements—each one playing a role.

Each of these elements is an object. They carry their own data. They know how to act. When needed, they interact with others. Because of this behavior, object orientation gives me a way to mirror the real world within software design.

What Are Objects?

So, what are objects?

At first glance, I think of everyday items: a chair, a house, or a car. Each of these is a complete unit, yet each one also consists of smaller components. Consider the following:

- A chair includes a backrest, a seat, and legs.

- A house contains walls, windows, and rooms.

- A car is built from wheels, an engine, and a body.

Books can also be seen this way—split into covers and pages. From this point of view, everything in my surroundings seems to be made of layered objects.

Object orientation doesn’t stop at physical things. It goes further, treating abstract ideas as objects too. For instance:

- Memberships

- Employment contracts

- Deliveries

- Office workflows

- Project phases

- Seasonal events

- Even winning the lottery or hiring someone

When I reflect on this, a surprising idea emerges: perhaps the world really is made up of objects. That realization is at the heart of object-oriented thinking.

Modeling with Objects

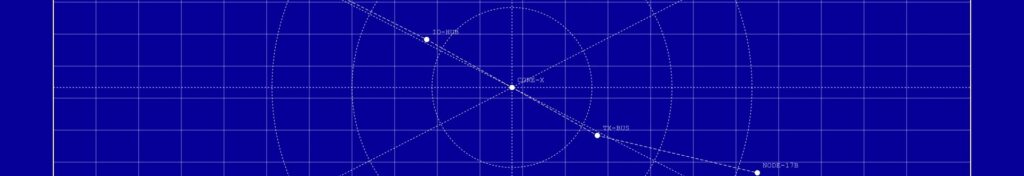

This concept leads directly to how I model systems. The world, in this mindset, becomes a structured collection of objects and their relationships. However, I don’t attempt to model the entire universe. Instead, I narrow my focus to a specific area—the part relevant to the problem I want to solve.

Say I’m developing a warehouse management system. Weather patterns or company holidays won’t matter. My focus remains tightly on the warehouse and its operations. That defines my context.

Within this context, I see an object as any unit I can clearly identify and separate from its surroundings. What counts as an object depends entirely on the scope of the problem. When I choose to model only what’s necessary, I reduce complexity and sharpen focus.

Real-world scenarios are rarely simple. They come with countless connections, variables, and interactions. It’s impossible to include everything in one model. That’s why I use abstraction. Abstraction lets me strip away irrelevant details while keeping essential ones.

The models I create this way don’t show the full picture. Still, they’re detailed enough to let me build functioning, useful systems. Computations based on these models are fast and targeted. Of course, the results only apply to the assumptions built into the model. That’s why I always interpret them in context, adjusting for the real-world situation afterward.

Objects in my model represent things I judge important. That judgment shapes the outcome. The better my understanding of the problem, the more accurate the model—and the more useful the results.

Final Thoughts

So, what are objects in object-oriented design? They’re more than just things I can touch. In object-oriented thinking, they’re the core elements of understanding and design. Whether I’m modeling a warehouse, a business process, or a hiring decision, I treat each of those elements as objects.

This approach allows me to focus on what matters. It keeps my systems simple, clear, and powerful. Object orientation, therefore, isn’t just a method—it’s a mindset.

And when I ask again what are objects, I now see them as everything I need to define, control, and connect to solve a real-world problem efficiently and effectively.

What’s Next?!

Now that you understand how requirements modeling connects business needs with object-oriented design, it’s time to explore the tools that make it all possible. In my next article, “Modeling Languages for Requirements Modeling,” I’ll introduce the most effective notations and diagrams used to express requirements clearly and consistently. Discover how the right modeling language can bring your ideas to life and help teams collaborate with precision from concept to implementation.

Credits: Photo with wood by Markus Winkler from Pexels

| Read more about draw.io |

|---|

| PDF Export VSDX Export HTML Export URL Export XML Export |