I define a goal as a desired future state that a person, group, or organization intends to achieve. It expresses an outcome rather than a specific action and provides direction for planning and decision-making. Therefore, a goal describes what “success” should look like and helps align effort, priorities, and behavior toward that intended state.

I define goals in requirements engineering as desired states of affairs that stakeholders want to achieve. In this context, I treat them as intentions. Therefore, I always ask: what situation do stakeholders want instead of the current one? First, I link goals to problems. For example, a problem shows that the current state prevents the desired outcome. Thus, I look for what stops it from happening now. Because problems and goals connect, I trace problems to find clear goals. Next, I trace goals to discover underlying problems.

I classify goals in families. For instance, goals may have parents and children. Consequently, I analyze causes to find parent goals. In addition, I inspect feasible solutions to reveal child goals. Moreover, I pay attention to siblings. Indeed, explicit goals often hide higher-level or lower-level goals. Therefore, I explore the full family to get a complete picture.

I use solutions as the bridge between problems and goals. In practice, a solution gives me a roadmap. Then, each action in that roadmap creates new lower-level goals. As a result, goal analysis and solution design go hand in hand. Furthermore, this approach helps me avoid jumping to obvious solutions that may not fit the context.

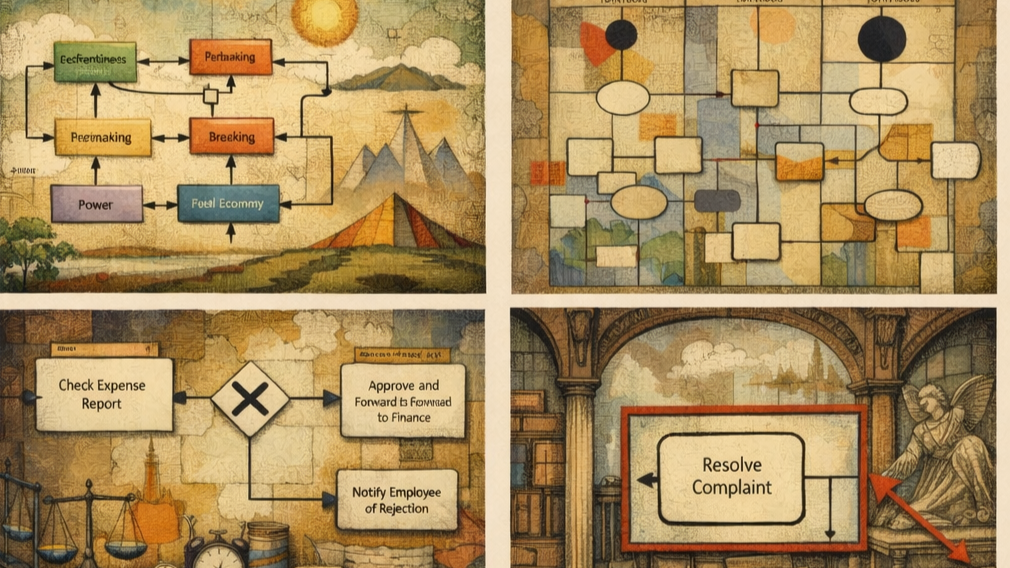

I document goals in text and in models. For example, I often use AND/OR trees to document goals at multiple levels. An AND relationship means that I must fulfill all subgoals. An OR relationship means that I must fulfill at least one subgoal. In addition, I use goal-oriented notations when needed. Thus, I apply GRL for modeling non-functional goals. Also, I use KAOS when I need to derive requirements from goal models. Moreover, I use the i* framework to model stakeholders, dependencies, and the socio-technical system.

I link goals to stakeholders, vision, and system scope. First, relevant stakeholders formulate the vision and the goals. Therefore, identifying a new stakeholder may change goals. Next, I use goals to guide stakeholder identification by asking who benefits or who gets affected. In addition, I use goals to define scope. For instance, I ask which elements are necessary to reach goals. If the scope changes, then the system may lose or gain means to fulfill goals. Consequently, I examine the impact of scope changes on goals. Thus, I balance vision, goals, stakeholders, and scope together.

I watch for conflicts among goals. However, I treat conflicts as signals. For example, conflicting goals indicate competing stakeholder intentions. Therefore, I negotiate priorities and refine goals. Meanwhile, I trace goals back to stakeholder behavior. In other words, I ask why the stakeholder has this intention. This reveals the rationale and helps me set measurable acceptance criteria.

I keep goal statements clear and testable. Furthermore, I refer each requirement to its motivating goal. As a result, I preserve traceability and rationale. Finally, I use goal thinking as a mindset. In short, I dig deeper into context before I propose a solution.